Harry Potter and the Basque Revision

Harry Potter and the Basque Revision

This year, Elkar Argitaletxea started republishing their Basque translations of Harry Potter—joyous news since they’ve been out of print for quite a while! However, as is sometimes the case, they took the opportunity to revisit the translation and make revisions to improve it. From their website:

Urteak ziren Harry Potter sortako lehen liburuak agortuta zeudela, baina arazo teknikoak geneuzkan berriz inprimatu ahal izateko. Hala ere, gaztetxoen irakurzaletasunean eta erreferentzia konpartituen transmisioan bilduma honek duen garrantzi itzela kontuan hartuta, eragozpen horiei aurre egin eta euskal irakurleei eskaini nahi diegu, berriz ere, Harry Potterren abenturak.

Hau ez da berrinprimatze hutsa, ordea. Itzulpena egin zenetik 25 urte pasatu direla kontuan hartuta, eta bitarte honetan euskal itzulpengintzaren mailak oso gora egin duela jakinda, testu guztien errebisio sakonari ekin diogu. Horretan aritu dira Iñaki Mendiguren jatorrizko lanen itzultzailea eta Maialen Berasategi Catalan, itzultzaile trebe, Harry Potterzale peto eta Berria egunkariko zuzentzailea. Emaitza, edizio berritu eta gaurkotu hau, txalogarria da zinez, lehendik ere ona zen testua bikain bihurtuz.

Possibly (like me) you don’t read Basque, so in English:

The first books in the Harry Potter series have been out of print for years and we had to solve some technical problems before we could reprint them. However, considering the great importance of this collection to young people’s literacy and the communication of shared references, we wanted to overcome these hurdles and offer Basque readers, once again, the adventures of Harry Potter.

This is not a mere reprint, however. Considering that 25 years have passed since the translation was made, and knowing that the level of Basque translation has increased greatly in the meantime, we have started a thorough revision of all the texts. This has been done by the original translator, Iñaki Mendigu, and Maialen Berasategi Catalan, a skilled translator, Harry Potter fan and editor of Berria newspaper. The result—this renewed and updated edition—is truly commendable, elevating an already good text into an excellent one.

The translation is courtesy of Google Translate and revised by me—forgive any errors on my part.

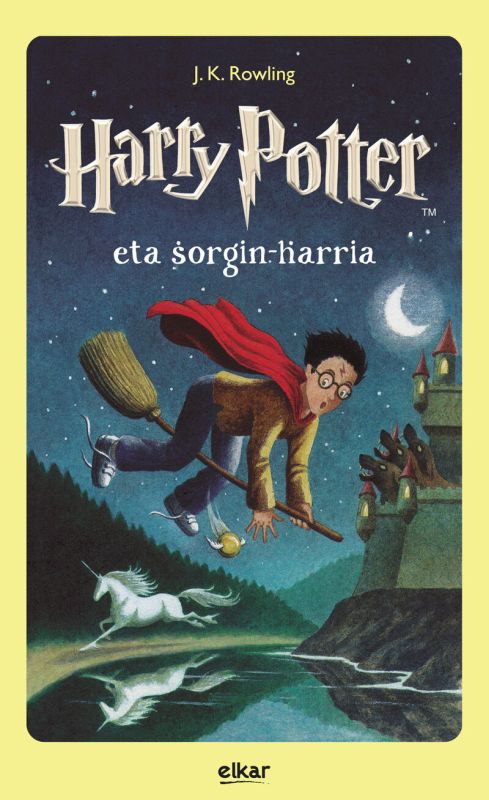

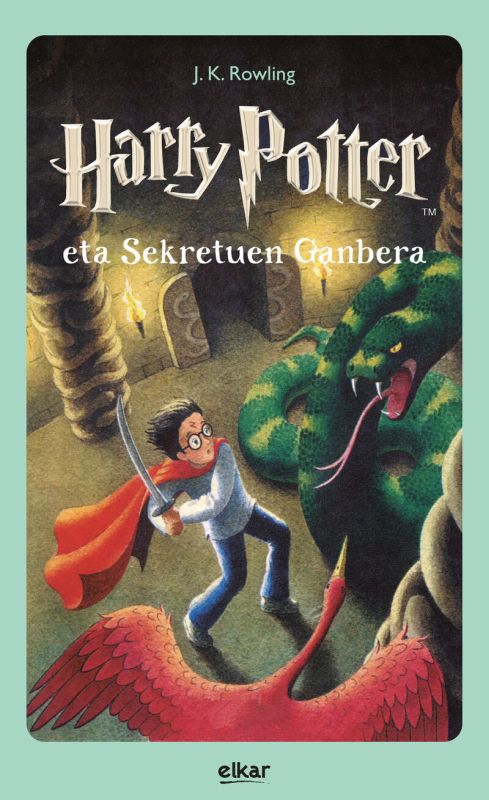

Thus far, The Philosopher’s Stone and Chamber of Secrets have come out.

| Title: | Harry Potter eta sorgin-harria |

| Translator: | |

| ISBN: | 978-84-1360-265-3 |

| Published: | 2023 |

| Publisher: | |

| Links: |

| Title: | Harry Potter eta sekretuen ganbera |

| Translator: | |

| ISBN: | 978-84-1360-266-0 |

| Published: | 2023 |

| Publisher: | |

| Links: |

Since I only collect Philosopher’s Stone, it’s the only one I have access to and I haven’t done a full textual comparison, but differences are immediately apparent. For instance, there are four chapter titles that have changed:

| English | Original Basque | Revised Basque | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | The Boy Who Lived | Bizirik geratutako mutikoa | Bizirik geratu zen mutikoa |

| 2. | The Vanishing Glass | Kristala desagertu | Beira desagertua |

| 3. | The Letters from No One | Inoren gutunak | Inor ez-en gutunak |

| 12. | The Mirror of Erised | Erised-eko ispilua | Arised-en ispilua |

Overall, I believe these differences are pretty subtle—that’s naturally the case with revisions. It’s seldom the case that there were genuine mistakes; usually revisions are about tweaking connotations and tone and consistency with what came later.

The difference in “The Boy Who Lived” is somewhat akin to the difference between “The Surviving Boy” and “The Boy Who Lived”—that is, the former is verb > adjective-like sort of construction and the latter is more properly a relative clause like it is in the original English.

The difference is “The Vanishing Glass” is kind of the opposite, at least with respect to the desagertu > desagertua change. It’s a change from a verb form to an adjectival form of “disappear”. Kristala > beira appears to just be a more natural vocabulary choice.

In “The Letters from No One”, the -en is a possessive marker like ‘s in English—inor can be both “somebody” and “nobody”—inor ez is more emphatically “nobody”/”no one”.

In the “Mirror of Erised”, the translator wasn’t originally aware of the “desire” connection—desira is the Basque word for “desire” so that fortunately made for a simple addition of that word-play. With respect to -eko and -en: whereas in English, we use ‘s to indicate belonging of any kind, Basque distinguishes between “origin” and “possession”. As a gross simplification, attached to E/Arised, -eko implies that Erised is a place and -en implies that Arised is something other than a location: a person, a group or even a concept. Although we’re never really told what “Erised” is, the word-play implies it’s more like “mirror of desire” than “mirror of (the city of) Erised” so the revision aligns better with that interpretation.

Although this is scant evidence indeed, my impression is that these changes are of a “source-orienting” nature making the translation a little closer to the English. According to the translator, they also made some changes based on the “newest rules of the Royal Academy” (a comment courtesy of @harrypotter_liburuak who has been in contact). As far as The List is concerned, these newly revised editions meet certainly meet my criteria for new linguistically-intresesting macroeditions.

Thanks to @harrypotter_liburuak who answered some questions and vetted my Basque assertions. Errors remain my own!