Revisiting the Spanish ‘Tykes’

Revisiting the Spanish ‘Tykes’

In 2016 I published “Harry Potter and the Spanish ‘Tykes’“—no exaggeration, that investigation was the beginning of a journey! It was a major reason for launching this website and it continues to be my most read and most reacted to article. It drew me into a larger community of collectors, many of whom sought my expertise and now I’m working on PotterLingual! But it all started with the Tykes.

That article was both revelatory and, in hindsight, a little naive. Up to that point, I had not given much consideration to textual variations within the published books—it was common knowledge that the English UK and English American books differed, that some texts had minor corrections and that Italian had undergone a systematic revision. But the fact that there had been regional adaptations of Spanish—three—was a little mind-blowing! Since then, more revisions—both significant and trivial—have been uncovered, demonstrating just how much floats up to the surface once you start dredging!

In part, due to the incredible engagement that the Tykes continues to enjoy, it became apparent Spanish was still being revised. Readers contributed identifications of their own editions based on my article and noted discrepancies—the first big one was the introduction of ‘diablito’ as a translation of ‘tyke’. It is similar to one of the previous four, ‘diablillo‘, that were one of the focuses of my first analysis (the other three being ‘chiquilín’, ‘tunante’ and ‘pillastre’). Unfortunately, that discovery coincided with a proliferation of new Spanish editions following the acquisition of the publisher, Salamandra, by the publishing giant Penguin Random House who started publishing the Harry Potter books in individual Spanish-speaking countries. Whereas in 2014-15, when the Tiago del Silva covers were first released, there was a clear pattern of three ISBNs that clearly corresponded to regional availability, there seemed to be any number of new ISBNs corresponding to who-knew-how-many countries.

Honestly, I just buried my head in the sand.

However, as ‘The List‘ continued to grow in content, the lack of Spanish editions became increasingly conspicuous—after all, potterglot.net is practically synonymous the Spanish ‘Tykes’… I finally bit the bullet and started to try and enumerate all the Spanish editions. Between the Penguin Random House websites (all regionalized!) and the Internet Archive, I painstakingly assembled a list of nearly 300 Spanish editions to be added to The List—and as of this writing, I believe it to be comprehensive. If any are missing, they are few and far between! Correct assignment to macroeditions—well that’s an entirely different question that will not be complete any time soon.

For the record, the books are being published in eight Spanish speaking countries now: Spain, Argentina, Colombia, Uruguay, Peru, Chile, Mexico and the United States. Inconsistently: while some books have ISBNs specific to each country, many overlap across regions. For example, certain Argentine editions are also sold in Chile and Peru. The overlaps were actually quite useful because they helped to establish that there were (until recently) three (and only three) publication regions with distinct texts.

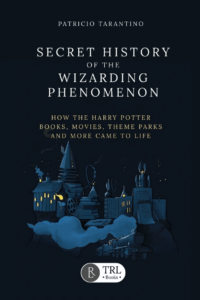

While reviewing the sixth chapter of Patricio Tarantino’s book Historia Secreta del Mundo Mágico (“Secret History of the the Wizarding Phenomenon”), titled Desembarco en español (“Landing in Spanish”)1, I found mention that a translator, María José Rodríguez Murguiondo was hired to ‘correct and unify’ the first three books. I asked him some questions, he shared his original interview notes with her… long story short, it provided some more specific insights into the timeline of edits that contradicted my original conclusions. Consequently, I finally decided to launch a more systematic and comprehensive analysis of what the heck is going on with the Spanish books.

In order to do so, I needed a lot more data. After much experimentation I have developed what I think is an effective—and more importantly, feasible—methodology for making comparisons. It includes some very objective, quantifiable measures2 that inform the more subjective decisions and it is applicable across translations. There will be more about that in the future, but for now, suffice it to say that I painstakingly assembled a corpus of the full text of PS Chapter 1 from 43 Spanish books. Not just different editions, but sometimes different printings of the same edition. The comparisons are illuminating.

Assumptions

In order for this investigation to be feasible, there are some assumptions that I had made and it’s important to keep them in mind. I have only compared Chapter 1—I am assuming that changes in the text of Chapter 1 are representative of changes made throughout the book. I’m assuming that there isn’t an edition that extensively revised, say, Chapter 12 without touching the text of any other chapter. However, it is certainly possible that other minor edits—particularly names or terms that don’t actually appear in Chapter 1 may have been made in editions that otherwise had identical first chapters.

I have quantified the differences between the texts and will be reporting percentages. Those are quite accurate and objective—for Chapter 1. I assume that changes to the rest of the book are of a similar scale.

I have thus far only looked at Philosopher’s Stone. We can’t directly extrapolate anything to the rest of the series, although I will assume that they have a similarly wild variation.

I definitely have not been able to acquire every text I would have liked to, let alone every print of every edition. So I’m assuming that the sampling I have is representative enough to identify the high-level patterns—enough to identify what we generally care about: ‘linguistically interesting macroeditions’. In my classification system, that means any macroedition but ‘variations’.

Conclusions

As this article got longer and longer, I decided it was necessary to include a summary of my conclusions with links to each discussion up front. Feel free to jump around but if you prefer to be lead down the garden-path, just continue reading with Conclusion #1.

Spoiler Alert!

| Conclusion | |

| #1: | The editors at Salamandra cannot resist tweaking the text of these books. |

| #2: | The original translation macroedition was Southern Cone and the SC ‘adaptation’ is actually a ‘revision’. |

| #3: | There is a tangled hierarchical relationship between the texts. |

| #4: | Spanish macroeditions include: 1 Translation, 4 regional adaptations, 3 revisions and 13 variants. |

| #5: | The EU adaptation was by far the biggest single edit of the original text. |

| #6: | The difference between the Latin American and European Adaptations are not that big. |

| #7: | There are two separate adaptations for Latin America. |

| #8: | Salamandra has recently disposed of the Southern Cone branch in favour of a Pan-America adaptation. |

| #9: | Some passages are more stable than others. |

You can also jump to Identifying Books or to my Book Bounty

Conclusion #1

The editors at Salamandra cannot resist tweaking the text of these books.

Of the 43 full-texts I acquired, there are 21 distinct texts. Those range from the removal of a single, one-letter word, a (“to”)3, to fully 20% of the text being different; as many as two-thirds of the lines being edited.

Conclusion #2

The original translation macroedition was Southern Cone and the SC ‘adaptation’ is actually a ‘revision’.

Back in 2016, I said: “it seems that this first edition was distributed throughout the Spanish speaking world without being regionalized.” I imagined a hierarchy that looked like this:

There was the original translation which I did not label as region specific because, although it was translated by a Southern Cone speaker and was likely identifiably Southern Cone Spanish, its target market was global4. Subsequently, I believed, as the popularity of Harry Potter increased, the text was then regionally adapted for three regions: Southern Cone (SC), Latin America (LA) and Europe (EU).

This was a reasonable model given what I knew at the time; however, I now know it is not accurate. I don’t believe that the original macroedition was intended to be sold outside of the Southern Cone. It isn’t 100% clear-cut for two reasons:

- the first edition, 978-950-04-1957-4, had print runs in Spain, and

- the Spanish Scholastic edition is a bit of an aberration—its text was a slightly edited variation of the original text and which may have been sold outside the Southern Cone.

I believe that the print runs in Spain had more to do with cost and resourcing—there was also a print-run of that edition in Brazil. For one thing, by the time those print runs occurred, they were already selling the first EU-adapted edition in Spain (978-84-7888-445-2). It came out in March, 1999—only three or four months after the original. I have a hard time believing that they would have two dramatically different texts for sale in the same market so close in time. It is much more plausible that they began the adaptation right away.

The first LA-adapted edition (978-84-7888-554-1) didn’t come out until July, 2000. Did Spanish speakers in the rest of the Americas have to wait more than a year to start reading HP or was the original book being sold across the region? The Scholastic edition suggests maybe? It came out in June 2000—but unfortunately it is not at all clear where it was being sold. Scholastic is an American company, of course, and likely they would have found a market for Spanish HP in the US; however, the only information is the book itself is De venta exclusiva en el mercado escolar (“Exclusively sold in the school market”), and Scholastic operates school book fairs and clubs in countries around the world. Availability of the book in the second-hand market is definitely predominantly the US—does that mean that Emecé was selling them throughout North and South America and that Scholastic picked up a school edition to sell in parallel similar to what Scholastic Canada did?

It’s conceivable, but I’m leaning towards not believing that’s what happened. I think that the rest of the Spanish-speaking world did have to wait and the reason is that when the LA editions started coming out, they all had specific distribution regions:

| 978-84-7888-554-1 | 2000-07 | Distribuido por Editorial Océano de México, S.A. |

| 978-84-7888-612-8 | 2000-07 | Distribuido en exclusivia por Editorial Océano S.A.5 |

| 978-84-7888-613-5 | 2000-09 | Distribuido por Editorial Norma, S.A. De venta exclusiza en Colombia, Ecuador, y Peru. |

Over the next couple of years, the distributors shifted somewhat (Lectorum was another major distributor), as did the country groups—it is clear that selling the books outside Argentina required different editions and distributor agreements. Similar restrictions still apply: it’s extremely difficult to get country-specific editions outside of the country itself. I rather expect this is because, in many of these countries, the books are sold considerably cheaper. This is the primary reason that I believe that the original edition was not distributed outside the Southern Cone; maybe not even Argentina. After the original and the Scholastic edition, only one other edition had the original text, and then only the first print of that edition: 978-84-7888-611-1. It came out October, 2000 and was for sale exclusively in Argentina and Uruguay—note the exclusion of Chile.

I don’t have a good explanation for why the Scholastic Edition has the original text if it was being sold in North America. Its ISBN suggests that it was planned after the first Mexican LA-adapted edition; perhaps Scholastic was impatient and the LA-adaptation wasn’t ready? The Scholastic edition only came out a month before, so I don’t find that plausible. The first LA adaptation and the EU are so close (more on that later), Scholastic could have just used the EU text. It’s possible the Scholastic editions were also only sold in the Southern Cone—Scholastic apparently operates in Argentina now (I haven’t been able to confirm whether they did in 2000). This one is still a mystery.

Ultimately, I think the evidence leans towards the original edition as being exclusive to the Southern Cone, if not Argentina. That means that the macroedition that I used to call the “Southern Cone adaptation” needs to be recategorized as a revision instead.

Conclusion #3

There is a tangled hierarchical relationship between the texts.

Of the 21 Spanish texts I have found (so far), many of them are not particularly interesting. Some only have a handful of changes, often just the correction of mistakes or tweaking of punctuation—stuff no one really cares about. What I find remarkable is just the number of times Salamandra has gone to the effort of re-editing the book! I think it’s normal after the first few prints to realize there are some errors and make corrections, or to decide at some point that larger scale review for consistency is in order; however, I believe most of the time, after a couple of reviews, the text is usually considered to be in a final state that doesn’t need to be edited for every new edition6.

Within my classification system, any change in the text constitutes a new macroedition. I don’t think we can get around that because I want ‘macroedition’ to be a completely objective definition and ultimately the judgment of what constitutes an interesting or significant change in a text is subjective. Where subjective judgment can legitimately play a role is in assigning a macroedition to a category. This is where the ‘variant’ category comes in: a ‘variant’ macroedition, in my system, is a change in text that exists, but is trivial enough to generally ignore. All the other ‘non-variant’ macroeditions are significant or ‘linguistically interesting’ which is the phrase I have often used in describing what my personal collection criteria are.

The question then becomes: how many of these 21 texts are merely variants and how many are actually of interest. Who decides that and how? Well… I decide it—presumptuous, I know, but it is my analysis! I do, however, aspire towards developing more objective measures and at least being transparent about my rationale for making those decisions. And, absolutely, if you disagree with me on any point, speak up and let’s talk about it!

In analyzing the macroeditions, it is important to not only place them into categories but to understand the relationship between them. An editor always has a starting point and so, inherently, macroeditions are hierarchical in nature; one is derived from another. In the simplest case, the hierarchy would be a straight, chronological line with each new macroedition being based on the one that came before. Although, The List doesn’t currently reflect these relationships, they are being captured behind the scenes. I am still struggling with how to display them effectively, especially since people may choose to ignore variants and should be able to do so.

How do you determine what macroedition was edited to produce what other macroedition7? The timeline helps—it’s pretty safe to assume that one was not based on another that was published later8. Once you have the publication order worked out (not always trivial), the question is simplified to which one of the preceding macroeditions was used as the base for a later macroedition. From there, it is about comparing the texts themselves and looking for unique edits—edits that seem unlikely to have been made more than once independently—and perhaps more importantly—looking for a pattern of multiple such edits. @baldurbabbling introduced us to the technical term for these patterns—Leitfehler—in his guest article about the Arabic translations. Judgment plays a big role and sometimes in ambiguous situations one has to rely on Occam’s Razor, merely choosing the simplest explanation.

It’s impossible to be 100% certain that this is the relationship between the macroeditions—there are few places where I think there was a little cross-contamination from edits being performed concurrently. However, I’m confident the diagram below is as close to reality as possible given the information I have. For the moment, don’t worry about the labels or colours—those details will come. Just absorb the structure and appreciate what a mess it is!

Conclusion #4

Spanish macroeditions include: 1 translation, 4 regional adaptations, 3 revisions and 13 variants.

Of the 21 texts, I classified 13 as variants—with edits minor enough that for most purposes, they can be ‘ignored’. ‘Ignored’, here, means that the editions that belong to the ‘variant’ can be considered, for all intents and purposes, as belonging to the variant’s closest non-variant ancestor. (It might be easiest to just look at the groupings in the table below—it’s awkward to describe in words, but intuitive to see.) I found 8 macroeditions that warrant other categorization—4 correspond directly to my 2016 macroeditions (with some tweaks) and 4 of them are brand new. Here’s a full list of before and after.

| 2016 Analysis | 2024 Analysis | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cat. | PGID | Description | Cat. | PGID | Label | Description | ||||

| 1. | Tr | SPA-Tr1 | Original – 1998 | 1. | Tr | SPA-Tr1 | SCTr|98 | Original – Southern Cone – 1998 | ||

| 2. | V | SPA-V59 | SCTr|00 | Original – Southern Cone – 2000 – Scholastic | ||||||

| 3. | V | SPA-V60 | SCTr|00b | Original – Southern Cone – 2000 – Emecé/Salamandra | ||||||

| 2. | A | SPA-A2 | Adaptation – Europe – 1999 | 4. | A | SPA-A2 | EUA1|99a | Adaptation – Europe – 1999 | ||

| 5. | V | SPA-V66 | EUA1|99b | Variant – Europe – 1999 – Book club | ||||||

| 6. | V | SPA-V67 | EUA1|99d | Variant – Europe – 1999 | ||||||

| 7. | V | SPA-V68 | EUA1|00 | Variant – Europe – 2000 | ||||||

| 8. | V | SPA-V69 | EUA1|08 | Variant – Europe – 2008 | ||||||

| 3. | A | SPA-A5 | Adaptation – Latin America – 2000 | 9. | A | SPA-A5 | LAA1|00 | Adaptation – Latin America – 2000 | ||

| 10. | V | SPA-V75 | LAA1|06 | Variant – Latin America – 2006 | ||||||

| 4. | A | SPA-A4 | Adaptation – Southern Cone – 2001 | 11. | R | SPA-R4 | SCR1|01 | Revision – Southern Cone – 2001 | ||

| 12. | V | SPA-V62 | SCR1|04 | Variant – Southern Cone – 2004 | ||||||

| 13. | R | SPA-R70 | EUR1|15 | Revision – Europe – 2015 | ||||||

| 14. | V | SPA-V71 | EUR1|18 | Variant – Europe – 2018 | ||||||

| 15. | V | SPA-V72 | EUR1|23 | Variant – Europe – 2023 | ||||||

| 16. | V | SPA-V74 | EUR1|24 | Variant – Europe – 2024 | ||||||

| 17. | R | SPA-R63 | SCR2|15 | Revision – Southern Cone – 2015 | ||||||

| 18. | V | SPA-V64 | SCR2|23e | Variant – Southern Cone – 2023 | ||||||

| 19. | A | SPA-A76 | LAA2|18 | Adaptation – Latin America – 2018 | ||||||

| 20. | V | SPA-V77 | LAA2|20b | Variant – Latin America – 2020 | ||||||

| 21. | A | SPA-A65 | PAA1|24 | Adaptation – Pan America – 2024 | ||||||

The macroeditions are in rough chronological order with the variants being grouped with their nearest non-variant parent and colour coded according to that parent. “Cat.” is short for the macroedition Category—that is Tr(anslation), A(daptation), R(evision), or V(ariant). “PGID” is a short form of the unique id (and link) for the macroedition in The List. The “Label” column contains the labels for each text that I used specifically for this analysis9. They are the labels used in the tree diagram above and they’ll appear again.

The labels consist of a macroedition group name + | + the year the macroedition first appeared + an optional letter. The ‘macroedition group’ is just like the grouping in the table: a single non-variant macroedition plus it’s associated variants. The ‘group name’ is the the two letter abbreviation of the Spanish region followed by the macroedition category and, with the exception of the ‘tr'(anslation), a single digit. The optional letter at the end is just to distinguish between published in the same year10. I will reference specific macroeditions by their full label, for example, SCTr|98—the very first text—but I will also reference the group by just it’s group name: ‘SCTr’ includes all of SCTr|98, SCTr|00, and SCTr|00b.

So where do we draw the line between a variant and a more significant macroedition? It comes down to two things:

- How big are the changes? (Scale)

- Why was it changed? (Motivation)

With respect to the scale of the differences, here is a comparison matrix / heat map that shows a direct measure of the difference between texts:

The diagonal is empty because those cell represent the comparison of a text to itself—they must be identical. The numbers above the diagonal are the same as below which is why the pattern of colours is also symmetrical on either side of the diagonal. Comparing LAA1|06 to EUR1|15 is equivalent to comparing EUR1|15 to LAA1|06. The smallest number in the matrix is 0%, the largest is 20%. Note that even if it says 0%, there are still differences between those two texts, they are just really, really small and round down to 0%.

There are a lot of numbers there and it isn’t immediately obvious how to interpret them; however, you can see that there are clear patterns—blocks of colour that correspond to patterns in the labels (naturally, since the final labels were chosen based on the final analysis!). I think the biggest take away from this table is that there is one really stark divide between the light purple-blue areas and the dark maroony areas and leads directly into…

Conclusion #5

The EU adaptation was by far the biggest single edit of the original text.

Fully 17.47% of chapter one (and presumably the rest of the books as well) was changed to prepare the book for introduction to the European market. 255/35511 lines of the text were edited in some manner. Five of the eight non-variant macroeditions, including all the other regional adaptations were derived from the EU adaptation. This is somewhat apparent in the tree diagram above, but it does not capture the magnitude of the difference. The difference between the SCTr and EUA1|99a is more than all of the other macroeditions combined (15.15%). I have started doing other comparisons with adaptations and revisions in other languages as well to try and get an idea of what the range of a ‘significant change’ is: generally that number looks to be about 2% ~ 6%. EUA1|99a is a really big change!

I have a third visualization—a ‘hierarchical clustering dendrogram’—that does a better job of capturing the magnitude of the differences between the texts and how they group together, albeit at the expense of the lineage.

The diagram is based on the numbers in the heat map—it uses a clustering algorithm that finds and links pairs of items that are the most similar to each other. Then it repeats the process on the pairs, linking them together until they all belong to one big group. The distance the connecting lines extend on the x-axis is proportional to their similarity—if it’s short, they are similar, if it’s long they are less similar.

The big divide between Southern Cone Spanish and the rest of the macroeditions is very clear—that connection is multiple times longer than the next longest. I added a vertical line at 1.5 on the scale—the idea being that if you cut all of the tree branches at that line, what you’re left with are the important clusters: macroedition groups consisting of a big edit plus some associated minor edits. Of course, 1.5 is a number I chose because it conveniently best matches the variant / non-variant macroedition clusters I’ve already decided on—it may be possible one day to set a more objective threshold, but for now that doesn’t exist.

The other important thing to note from the dendrogram is that one of my macroeditions is not like the others. Even with my conveniently selected threshold line, EUA1 and LAA1 look like they belong together.

Conclusion #6

The difference between the Latin American and European Adaptations are not that big.

It’s worthwhile to look actual numbers again. Here is a list of the ‘big edits’ that correspond non-variant macroeditions and the percentage of the text that changed:

| Parent | Child | Difference |

|---|---|---|

| SCTr|00 | EUA1|99a | 17.47% |

| EUA1|99d | LAA1|00 | 0.39% |

| SCTr|00b | SCR1|01 | 2.60% |

| EUA1|08 | EUR1|15 | 2.99% |

| SCR1|04 | SCR2|15 | 2.36% |

| EUR1|18 | LAA2|18 | 1.28% |

| LAA2|20b | PAA1|24 | 2.88% |

The first Latin American adaptation was not a huge departure. In fact, there are three larger edits (0.69%, 0.50%, and 0.41%) that I still categorize as variants and not revisions. Why? Because ‘scale‘ is not the only consideration. ‘Motivation‘ is the other piece—why is the text being edited? That involves examining the actual changes and trying to understand the context the changes are happening in a bit better. From the comparisons that I have done in Spanish and other languages, I’m getting the impression that >2% of a difference is well into ‘linguistically interesting’ territory. Less than 2% demands a more nuanced investigation.

I can’t deny that there is a lot of ambiguity here. I’m not a native speaker of Spanish, let alone an expert on the details of the regional variations of Spanish; however, the observations that I made in 2016 all still stand—the changes made between EUA1 and LAA1 were, by and large, tailoring the text to a different Spanish dialect. Adaptation for different language communities will always be of interest to me. Although the changes are minimal, they tell you something about the difference between the Spanish spoken in one region vs. another—that’s kind of the definition of ‘linguistically interesting’. Therefore, in my opinion, 0.39% makes the cut.

By contrast, many of the changes in the more-divergent variants seem arbitrary. They don’t seem to be improving the translation or making systematic changes—my impression was often just that each editor just wanted to make their mark on the book. Others may disagree and I’d love to hear about it!

Conclusion #7

There are two separate adaptations for Latin America.

If you’ve been paying attention you will have noticed by now, that there is a discontinuity in the Latin American books—they were adapted twice from the EU editions! Although my original SPA -> (SPA-SC, SPA-EU, SPA-LA) tree was wildly naive, for a period of 18 years or so it approximated the reality: we still had a tree that nicely branched out into three different regions that seemed to be, as you’d expect, developing independently of each other.

Around 2015, it seems, Salamadra decided it was time to revise Piedra Filosofal across the board. Perhaps not coincidentally, this seems to have coincided with the first editions that did not have Delores Avendaño‘s iconic cover art. The Tiago del Silva covers came out in 2014 and 2015, as did the Jim Kay illustrated edition. 2015 is my anchor year for these changes despite the EU Tiago del Silva first being published in 2014, because the only print I’ve seen was 2015 and my investigation has shown that, although there is a high-degree of correlation between ISBN’s and macroeditions in Spanish, it is by no means perfect.

In fact, LAA2|18 was profoundly confusing for a long time. Originally, I was organizing my texts by the edition year—in this case, we’re talking about 978-84-9838-438-3, an otherwise unremarkable bolsillo (“trade paperback”) originally published in 2012 and that I labelled ‘LA12’. It was clearly an LA edition, but it was a dramatic departure from my, then, ‘LA06’ (LAA2|06). Compared to EUR1, the differences are relatively minimal, but LAA1|06 <> LAA2|18 is 3.78%! 2012 was well before the Tiago del Silva covers came out, which was the first appearance of both EUR1 and SCR2. It appeared that ‘LA12’ (LAA2|18) was basis for EUR1 but the LA Tiago del Silva was still 100% the 2006 text! It wasn’t until I managed to get a hold of a couple of earlier prints of 978-84-9838-438-3 that it became clear that the order was reversed and that I needed to focus on print-dates not edition dates.

It’s possible that my years are still off—their purpose is to relatively order the changes and to distinguish the texts in as few characters as possible. Unfortunately until I find the exact printing that marks the change, I won’t know for sure and the first appearance may be earlier. It is mystifying to me that they went to the effort of revising SC and EU for the Tiago del Silva covers, but didn’t get to LA for a couple more years? Clearly, there’s not a neurodivergent in the bunch of them at Salamandra!

As to why they chose readapt LA rather than revise it: my best guess is that it seemed the path of least resistance—that it seemed easier to start with the revised text and adapt it again rather than try to apply some of those revisions to the existing text.

Conclusion #8

Salamandra has recently disposed of the Southern Cone branch in favour of a Pan-America adaptation.

In 2019, Salamandra changes hands again and became a subsidiary of Penguin Random House. With the change came an explosion of editions as they started producing books with country-specific ISBNs—they still conformed to the three regional texts; Penguin Random House’s production and distribution chain just has wider reach. They certainly don’t seem to need the same distribution agreements that Salamandra worked with for so long.

It appears that Penguin has decided that three regions is too much of a nuisance though and with the new Xavier Bonet editions, they have dispensed of the Southern Cone branch to create a new Pan-American adaptation based on the second Latin American adaptation12.

The difference between LAA2 and PAA1 is on the scale of the other revisions and adaptations that we’ve seen before: 2.88%. However, consider that for Southern Cone readers, the relevant comparison is not between PAA1 and its parent LAA2, it is between PAA1 and SCR2, the last text distributed in their region—mostly likely still widely available. That difference is %18.73—and unlike the 17.47% jump to EUA1, this change is within the same market. Remarkably, thus far it seems to have not been commented on—Patricio Tarantino told me that he hasn’t come across any discussion in Spanish sources online.

Conclusion #9

Some passages are more stable than others.

72 lines (of 355) remained completely untouched across all the macroeditions—some of them quite long. For example:

| Lns. 75 & 76 | Al contrario, su rostro se iluminó con una amplia sonrisa, mientras decía con una voz tan chillona que llamaba la atención de los que pasaban: —¡No se disculpe, mi querido señor, porque hoy nada puede molestarme! |

| Eng. | On the contrary, his face split into a wide smile and he said in a squeaky voice that made passers-by stare: “Don’t be sorry, my dear sir, for nothing could upset me today! |

| Ln. 289 | La profesora McGonagall abrió la boca, cambió de idea, tragó y luego dijo: —Sí… sí, tiene razón, por supuesto. |

| Eng. | Professor McGonagall opened her mouth, changed her mind, swallowed and then said, “Yes — yes, you’re right, of course. |

On the other side of the spectrum, there were two lines that had a total of 9 different variants. The first (Ln. 155), describing the cat on Privet Drive, I’ve laid out below.

| Ln. 155 | It didn't so much as quiver when a car door slammed in the next street, nor when two owls swooped overhead. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | SCTr|98 | Apenas tembló cuando se cerró la | puerta | de un | coche | en la | calle siguiente, | ni | cuando dos | lechuzas | bajaron | sobre su cabeza. | |||||||||||||||||||

| 2 | SCR1|01 | Apenas tembló cuando se cerró la | puerta | de un | coche | en la | cuadra siguiente | ni | siquiera | pestañeó | cuando dos | lechuzas | bajaron | sobre su cabeza. | |||||||||||||||||

| 3 | SCR2|15 | Apenas tembló cuando se cerró la | puerta | de un | coche | en la | cuadra siguiente, | ni | siquiera | pestañeó | cuando dos | búhos | bajaron | sobre su cabeza. | |||||||||||||||||

| 4 | EUA1|99a | Apenas tembló cuando se cerró la | puertezuela | de un | coche | en la | calle de al lado, | ni | cuando dos | lechuzas | volaron | sobre su cabeza. | |||||||||||||||||||

| 5 | EUA1|99b | Apenas tembló cuando se cerró la | portezuela | de un | coche | en la | calle de al lado, | ni | cuando dos | lechuzas | volaron | sobre su cabeza. | |||||||||||||||||||

| 6 | LAA1|00 | Apenas tembló cuando se cerró la | puerta | de un | coche | en la | calle de al lado, | ni | cuando dos | lechuzas | volaron | sobre su cabeza. | |||||||||||||||||||

| 7 | EUR1|15 | Apenas tembló cuando se cerró la | puerta | de un | coche | en la | calle de al lado, | ni | cuando dos | búhos | volaron | sobre su cabeza. | |||||||||||||||||||

| 8 | LAA2|18 | Apenas tembló cuando se cerró la | puerta | de un | auto | en la | calle de al lado, | ni | cuando dos | búhos | volaron | sobre su cabeza. | |||||||||||||||||||

| 9 | PAA1|24 | Apenas tembló cuando se cerró la | puerta | de un | auto | en la | calle de al lado, | ni | cuando dos | lechuzas | volaron | sobre su cabeza. | |||||||||||||||||||

On the whole, the sentences are not that different—in fact, looking purely at the comparison numbers, Ln. 155 doesn’t stand out. What is notable, is how many times editors came back to this sentence and thought, “something is awkward here” and tried to improve it.

A few comments about the choices made here13:

- Puerta (“door”) is more neutrally “door” than puertezuela/portezuela which are more speficially smaller doors.

- Coche (“car”) is common in the EU and apparently parts of Latin America, but auto is more universal across all Spanish-speaking regions. I was a little surprised that carro never appeared—that was the first word I learned for “car” in Spanish.

- Siguiente is literally “next” as in sequence regardless of context; de al lado (“next door”, “to the side”) brings a specifically spatial connotation to the phrase.

- Calle (“street”) is general and universal; where as cuadra (“block”) is more region-specific.

- Lechuzas vs. búhos—one of the original variations that I first noticed. Both mean “owl”, but lechuzas are more specifically barn ows and búhos are more like Hedwig. I find it ironic that they very deliberatly replaced lechuzas with búhos across all three regions in the circa-2015 major revision only to swap it back again in the new Pan American adaptation!

- Bajaron seems to be more accurately “swoop” vs. volaron which is more generically “fly”—honestly, I’m at a loss as to why they wouldn’t have stuck with bajaron.

An optional diversion about ni siquiera pestañeó (click to read)

It is a bit of a diversion, but ni siquiera pestañeó (“didn’t even blink”) deserves more comment: the motivation to insert this phrase that didn’t exist in the English is interesting. It could be that it adds a certain amount of drama or emphasis McGonagall’s stoicism—siquiera (“even”) correctly implies that two owls swooping at you is more flinch-worthy than a car door slamming far away. However, my intuition is that it has more to do with cadence, symmetry and semantic complexity.

There is ample evidence that simpler syntactic structures are easier to understand. Compare these two syntactic trees representing the sentence first without siquiera pestañeó and then with:

These are extremely simplified tree diagrams, but they illustrate an important point about distance. The clauses beginning with cuando (“when”), modify the closest verb. In the first sentence, there is only one verb, tembló (“quiver”) and both clauses modify. The second clause is “further away” because the first clause is inbetween—there’s kind of a long distance relationship there that increases the “complexity” and the effort required to parse and understand the sentence. On the other hand, by introducing the second verb, pestañeó (“blink”), for the second clause to modify, the structure changes completely to one in which two sentences are conjoined and there are no long-distance relationships.

There’s more to this change: in terms of intonation and prosody, there is a pattern applied to the an entire sentence. The introduction of siquiera pestañeó breaks one long prosodic sentence into two shorter ones that mimic each other allowing for a more dynamic (and hence more interesting) progression. I also do not believe it is coincidental that after the original insertion14 the two sentences have almost the same number of syllables: Apenas…siguiente (24) and ni…cabeza (23). Syntactically, rhythmically and intonationally more symmetry was introduce into the passage.

I doubt the editor was consciously aware of what they were doing by adding siquiera pestañeó—it probably simply “sounded better”. There is always a tension in translation between being true to the words of the original, being true to its meaning, and the artful expression of these in a different language. When we see the introduction of material that is not in the original, our initial reaction is often to cock and eyebrow; however, you can bet that it made some sort of “improvement”, even if it is purely an aesthetic one.

The second 9-variation line (Ln. 303)—the initial description of Hagrid—is unfortunately too long to coerce into a similar table but I’ve included it below as best as I can along with three lines that had 8-variants each. I have bolded the differences between one sentence and the next—keep in mind that these are ordered by region so the highlighted changes are not between parent and child texts. ‘␣‘ indicates a deletion.

You’ll notice that in many cases the only difference is the use of commas. I took the texts as is, punctuation and all; partly because it was simpler and partly because I don’t want to make any assumptions in advance as to what might turn out to be notable. Generally I don’t think that punctuation use is notable and perhaps I’ll figure out a reasonable method to exclude or control for them; for the time being, they are in the data and possibly have unjustly emphasized the passages I am calling ‘unstable’. I do think it is a little amusing just how much they waffle back and forth on where commas belong sometimes.

Ln. 303

| Ln. 303 | He looked simply too big to be allowed, and so wild — long tangles of bushy black hair and beard hid most of his face, he had hands the size of dustbin lids and his feet in their leather boots were like baby dolphins. | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SCTr|98 | Simplemente era demasiado grande para que lo aceptaran y tan salvaje: cabello largo enmarañado, de color negro y una barba que le cubría casi toda la cara; las manos eran del tamaño de las tapas del cubo para basura y sus pies, con botas de cuero, eran como bebés de delfines. |

| 2 | SCTr|00 | Simplemente era demasiado grande para que lo aceptaran y tan salvaje: cabello largo enmarañado, de color negro, y una barba que le cubría casi toda la cara; las manos eran del tamaño de las tapas del cubo para basura y sus pies, con botas de cuero, eran como bebés de delfines. |

| 3 | SCR1|01 | Simplemente era demasiado grande ␣ ␣ ␣ ␣ y tan salvaje: cabello largo enmarañado, de color negro; ␣ una barba que le cubría casi toda la cara; las manos eran del tamaño de las tapas del cubo para basura, y sus pies, con botas de cuero, eran como bebés de delfines. |

| 4 | SCR2|15 | Simplemente era demasiado grande y tan salvaje: cabello largo enmarañado, de color negro; una barba que le cubría casi toda la cara; las manos eran del tamaño de las tapas del tacho de basura, y sus pies, con botas de cuero, eran como bebés de delfines. |

| 5 | EUA1|99a | Se podía decir que era demasiado grande para que lo aceptaran y, además, tan desaliñado… Cabello negro, largo y revuelto, y una barba que le cubría casi toda la cara. Sus manos tenían el mismo tamaño que las tapas del cubo de la basura y sus pies, calzados con botas de cuero, parecían crías de delfín. |

| 6 | EUR1|18 | Se podía decir que era demasiado grande y ␣ ␣ ␣ ␣, además, tan desaliñado… Cabello negro, largo y revuelto, y una barba que le cubría casi toda la cara. Sus manos tenían el mismo tamaño que las tapas del cubo de la basura y sus pies, calzados con botas de cuero, parecían crías de delfín. |

| 7 | LAA2|18 | Se podía decir que simplemente era demasiado grande para que lo aceptaran y, además, tan desaliñado… Cabello negro, largo y revuelto, y una barba que le cubría casi toda la cara. Sus manos tenían el mismo tamaño que las tapas del bote de la basura y sus pies, calzados con botas de cuero, parecían crías de delfín. |

| 8 | LAA2|20b | Se podía decir que simplemente era demasiado grande ␣ ␣ ␣ ␣ y, además, tan desaliñado… Cabello negro, largo y revuelto, y una barba que le cubría casi toda la cara. Sus manos tenían el mismo tamaño que las tapas del bote de la basuray sus pies, calzados con botas de cuero, parecían crías de delfín. |

| 9 | PAA1|24 | Sencillamente se podía decir que ␣ era demasiado grande para ser real y, además, tan desaliñado… Cabello negro, largo y revuelto, y una barba que le cubría casi toda la cara. Sus manos tenían el mismo tamaño que las tapas del bote de la basura y sus pies, calzados con botas de cuero, parecían crías de delfín. |

Ln. 98

| Ln. 98 | “And finally, bird-watchers everywhere have reported that the nation’s owls have been behaving very unusually today. | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SCTr|98 | —Y por último, observadores de pájaros de todas partes, han informado que hoy, las lechuzas de la nación han tenido una conducta poco habitual. |

| 2 | SCR1|01 | —Y por último, observadores de pájaros de todas partes han informado que hoy las lechuzas ␣ ␣ ␣ han tenido una conducta poco habitual. |

| 3 | SCR2|15 | —Y por último, observadores de pájaros de todas partes han informado que hoy los búhos han tenido una conducta poco habitual. |

| 4 | EUA1|99a | —Y, por último, observadores de pájaros de todas partes han informado de que hoy las lechuzas de la nación han tenido una conducta poco habitual. |

| 5 | EUR1|15 | —Y, por último, observadores de pájaros de todas partes han informado de que hoy los búhos del país han presentado una conducta poco habitual. |

| 6 | LAA1|00 | —Y, por último, observadores de pájaros de todas partes han informado ␣ que hoy las lechuzas de la nación han tenido una conducta poco habitual. |

| 7 | LAA2|18 | —Y, por último, observadores de pájaros de todas partes han informado que hoy los búhos del país han presentado una conducta poco habitual. |

| 8 | PAA1|24 | —Y, por último, observadores de pájaros de todas partes han informado que hoy las lechuzas del país han presentado una conducta poco habitual. |

Ln. 235

| Ln. 235 | It seemed that Professor McGonagall had reached the point she was most anxious to discuss, the real reason she had been waiting on a cold hard wall all day, for neither as a cat nor as a woman had she fixed Dumbledore with such a piercing stare as she did now. | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SCTr|98 | Parecía que la profesora McGonagall había llegado al punto que más ansiosa estaba por discutir, la verdadera razón por la que había esperado todo el día en una fría pared, porque ni como gato, ni como mujer, había mirado con tal intensidad a Dumbledore como lo hacía ahora. |

| 2 | SCR1|01 | Parecía que la profesora McGonagall había llegado al punto que más ansiosa estaba por discutir, la verdadera razón por la que había esperado todo el día en una fría pared, porque ni como gato␣ ni como mujer, jamás había mirado con tal intensidad a Dumbledore como lo hacía ahora. |

| 3 | EUA1|99a | Parecía que la profesora McGonagall había llegado al punto que más deseosa estaba por discutir, la verdadera razón por la que había esperado todo el día en una fría pared␣ pues, ni como gato ni como mujer, había mirado nunca a Dumbledore con tal intensidad como lo hacía en aquel momento. |

| 4 | EUR1|15 | Parecía que la profesora McGonagall había llegado al punto que más deseosa estaba por discutir, la verdadera razón por la que había esperado todo el día en una fría tapia, pues, ni como gato ni como mujer, había mirado nunca a Dumbledore con tal intensidad como lo hacía en aquel momento. |

| 5 | EUR1|18 | Parecía que la profesora McGonagall había llegado al punto que más deseosa estaba por discutir, la verdadera razón por la que había esperado todo el día en una fría tapia, pues, ni como gato ni como mujer␣ había mirado nunca a Dumbledore con tal intensidad como lo hacía en aquel momento. |

| 6 | EUR1|23 | Parecía que la profesora McGonagall había llegado al punto que más deseosa estaba por discutir, la verdadera razón por la que había esperado todo el día en una fría tapia, pues␣ ni como gato ni como mujer había mirado nunca a Dumbledore con tal intensidad como lo hacía en aquel momento. |

| 7 | LAA2|18 | Parecía que la profesora McGonagall había llegado al punto que más deseosa estaba por discutir, la verdadera razón por la que había esperado todo el día en una fría tapia␣ pues, ni como gato ni como mujer, había mirado nunca a Dumbledore con tal intensidad como lo hacía en aquel momento. |

| 8 | PAA1|24 | Parecía que la profesora McGonagall había llegado al punto que más deseosa estaba por discutir, la verdadera razón por la que había esperado todo el día en una fría pared, porque jamás, ni como gato ni como mujer, había mirado nunca a Dumbledore con la intensidad con que lo hacía en aquel momento. |

Ln. 253

| Ln. 253 | No one knows why, or how, but they’re saying that when he couldn’t kill Harry Potter, Voldemort’s power somehow broke — and that’s why he’s gone.” | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | SCTr|98 | Nadie sabe por qué, o cómo, pero dicen que cuando no pudo matar a Harry Potter, el poder de Voldemort se quebró… y es por eso que se ha ido. |

| 2 | SCR1|01 | Nadie sabe por qué, o cómo, pero dicen que cuando no pudo matar a Harry Potter, el poder de Voldemort se quebró… y por eso es que se ha ido. |

| 3 | SCR2|15 | Nadie sabe por qué, o cómo, pero dicen que, como no pudo matar a Harry Potter, el poder de Voldemort se quebró… y que ésa es la razón por la que se ha ido. |

| 4 | EUA1|99a | Nadie sabe por qué, ni cómo, pero dicen que␣ como no pudo matarlo, el poder de Voldemort se rompió… y que ésa es la razón por la que se ha ido. |

| 5 | EUR1|15 | Nadie sabe por qué, ni cómo, pero dicen que, como no pudo matarlo, el poder de Voldemort se rompió… y que ésa es la razón por la que se ha ido. |

| 6 | LAA1|00 | Nadie sabe por qué␣ ni cómo, pero dicen que␣ como no pudo matarlo, el poder de Voldemort se rompió… y que ésa es la razón por la que se ha ido. |

| 7 | LAA2|18 | Nadie sabe por qué ni cómo, pero dicen que, como no pudo matarlo, el poder de Voldemort se rompió… y que ésa es la razón por la que se ha ido. |

| 8 | PAA1|24 | Nadie sabe por qué ni cómo, pero dicen que, como no pudo matarlo, el poder de Voldemort se rompió… y que esa es la razón por la que se ha ido. |

To be honest, I can’t say whether there is something inherently ‘stable’ or ‘unstable’ about the language in these sentences or passages. My intuition leads me to believe that there is; that stability is about how natural text feels to a Spanish speaker. There will always come a point in translation where the translation is ‘correct’ in that it is grammatical and has the intended meaning, but there is something ineffable about the feeling. Maybe it requires a less common word or one that has slighly different connotations. Maybe it’s simply not something that a native speaker would say even though there’s nothing actually exactly wrong with it. I think that passages that are just ever-so-slighly unnatural are likely the ones that receive more attention from editors.

But native-speakers: you tell me!

Identifying Books

There are way too many editions and prints to try and list them all here. HP1-SPA-iv is going to be your go-to resource15. of course it is by no means complete. As before, I would be grateful for any contributions anyone can make! If you have one of the unidentified editions or book prints on the list, please do contact me. I do have a few rules of thumb for the groups that you can follow though:

| Group | Confirmed | Approx Date Range |

|---|---|---|

| SCTr | 978-950-04-1957-4 978-84-7888-548-0 978-84-7888-611-1 – first print only | 1998 ~ 2000 |

| SCR1 | 978-84-7888-611-1 – from second print 978-84-7888-779-8 978-84-7888-861-0 978-84-9838-017-0 978-84-9838-012-5 978-84-9838-437-6 | 2001 ~ 2012 |

| SCR2 | 978-84-9838-656-1 978-1-78939-201-2 | 2015 ~ 2023 |

| EUA1 | 978-84-226-7987-5 978-84-7888-445-2 – up to Pr. 51 978-84-9838-266-2 – first print | 1999 ~ 2010 |

| EUR1 | 978-84-9838-631-8 978-1-78110-131-5 978-84-9838-887-9 978-84-7888-445-2 – from Pr. 80 978-84-19275-30-1 978-84-19275-80-6 | 2014 ~ 2024 |

| LAA1 | 978-84-7888-613-5 978-84-7888-554-1 978-84-7888-654-8 978-84-7888-759-0 978-84-9838-438-3 – up to Pr. 6 978-84-9838-694-3 | 2000 ~ 2015 |

| LAA2 | 978-84-9838-438-3 – from Pr. 16 978-612-4497-07-0 978-1-64473-207-6 | 2018 ~ 2023 |

| PAA1 | 978-607-384-414-7 978-987-800-209-5 978-956-6075-75-2 | 2024 |

If the print isn’t qualified for an ISBN, I believe that all of the prints belong to the same group, mostly judging by the dates. However, I can’t always be sure what the last print of an edition actually is, so if your print is outside the date range I’ve provided or even on the edge, it would be best to check with me.

If the print is qualified for the ISBN, what I have provided is what I have confirmed. For instance, 978-84-7888-445-2 has been continuously published from 1999 ~ 2024 despite revisions in the text. When I say, up to print 51 for EUA1 and from print 80 for EUR1, I mean that I know the transition happened somewhere in the 29 print in between but I don’t know what the cutting point is. If you have one of those prints contact me and we’ll see if we can’t narrow the range down!

If you have a book/print that isn’t listed under HP1-SPA-iv yet, do let me know and we’ll identify and add it. If you have one that looks like it hasn’t been identified there, or looks like it was misidentified there, let me know. If you’re trying to identify a book you’re buying and it’s not on the list, if it’s in the middle of the date range, I think you can be pretty confident about identifying it—on the edges… no guarantees!

Book Bounty

There are a few books that I decided I wanted to get because sometimes I can’t quite keep my compulsive-collecter mind under control. I want to complete a set of Emecé-published books and the books with ISBNs that crossed over between Emecé and Salamandra. They’re hard to track down mostly because although the ISBNs are in some cases very common it’s pratically impossible to find accurate listings in the second-hand market when you are looking for specific prints. So if you happen to have one of these books and are willing to part with it (or trade!) please let me know:

| ISBN | Publisher | Date | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 978-84-7888-561-9 | any (but I think there’s only 1) | Emecé | 2000 |

| 978-84-7888-612-8 | up to about 4th print? | Emecé | 2000 |

| 978-84-7888-612-8 | about 4th print? | Emecé on copyright and Salamandra on the cover | 2000 |

| 978-84-7888-611-1 | 1st print | Emecé on copyright and Salamandra on the cover | 2000 |

| 978-84-7888-613-5 | 1st print | Emecé | 2000 |

| 978-84-7888-613-5 | from 3rd print | Salamandra | 2000-2001 |

| 978-84-7888-445-2 | 17th print | Emecé on copyright and Salamandra on the cover | 2000 |

| 978-84-7888-642-5 | 1st print | Salamandra | 2000 |

| 978-84-7888-770-5 | any | Salamandra | 2002 |

| 978-84-9838-657-8 | any | Salamandra | 2015 |

Acknowledgements

An investigation of this scope does not happen without support. I would like to thank @aroundtheworld_withharrypotter, @harrypotter_liburuak, @baldur, Patricio Taratino, and all of those individuals that contributed photos and book identifications since The Spanish ‘Tykes’ was first published!

Notes

- The chapter is about the publication of the books in Spanish and it didn’t make it into the English translation of the book. ↩︎

- For anyone who needs justification now, the primary measure I am using is the Levenshtein difference calculated line-by-line, then summed and divided by the total number of characters in the compared text. ↩︎

- That single-word removal actually raises some genuinely interesting linguistic and philosophical questions, but that’s a story for another time. ↩︎

- Similarly, at least on my list, I have English and English, American even though the “English” is obviously UK English. The target market for English is not just the UK; it sold all over the world—just not in the US where the book was adapted. ↩︎

- Appears to be Central America and the Caribbean. ↩︎

- Of course, I’ve never looked this closely at any other set of editions so maybe that’s naive… ↩︎

- There is an entire academic discipline, Textual Criticism, in particular Stemmatology that is devoted to precisely this question. Stemmatology is the study of the relationships and development of texts or manuscripts, particularly in terms of how they branch and evolve from a common source. It involves reconstructing the “family tree” of a text’s transmission by analyzing how copies and versions of a manuscript have diverged over time. This is by no means a field I have been trained in—in fact, I was only introduced to it last year by @baldurbabbling, my guest author who wrote: Harry Potter and the Ever-Transfigured Arabic Translation. I was a ‘stemmalologist’ long before I knew it! Consequently, keep in mind I am a novice perhaps reinventing the wheel! And if any experts in Textual Criticism (Baldur included!) happen to come across this analysis—I apologize for bumbling around in your field: feedback is certainly appreciated. ↩︎

- It is conceivable of course—one could contrive a complex scenario in which a series of edits occurred, only the final of which was published, and then for some reason and earlier edit was subsequently published. I think a scenario like that would be extremely unlikely. ↩︎

- Mea culpa—theoretically, this is the kind of purpose it would be ideal to use PGIDs for! So why do I have additional labels too? The PGIDs are a trade of of informative and unchanging and frankly, working with as many texts as I have been, I needed more informative. Plus, there was a chicken-or-the-egg problem: the PGIDs come from my database, but the analysis needed to be done before adding anything to the database. ↩︎

- The letters may seem random but keep in mind I had a total of 43 texts and only 21 were distinct and made it into the analysis but nonetheless were labelled. ↩︎

- I don’t want to get into the methodology in this article—just think of Chapter 1 having 355 sentences. ↩︎

- It is possible it began with the iridescent 25th anniversary Johnny Duddle editions but I haven’t been able to inspect them yet. ↩︎

- Thanks to @contrabassoon for letting me bounce my non-fluent impressions off him! ↩︎

- SCR1|01 which uses lechuzas not buhós. ↩︎

- TheList required some updates in order to handle the display of variant macroeditions and there are still some little quirks I’m not sure how to figure out. On any page that there are filters, you can turn the display of variants on and off; however, there is also a global option that can be changed in the new “options” pull tab on the right. When checked, that will change the default for filters, but also the display of macroedition and edition records. Turning the variants on or off doesn’t just hide or show them; in either case all editions and books still appear. What changes is which macroedition they appear to be attached to: their actual variant or the non-variant macroedition it was derived from. ↩︎

So exciting! What a passion behind this incredible story. Thanks!

It’s a comprehensive study! Focusing on significant points (multi-dimensional)! I need to keep reading to learn more about it! Lovely and so encouraging!

Phenominal! I’ve done all the audiobooks in Spanish that came out post-2020 with my kids, in both Latin American and European Spanish, and I’ve read various Spanish versions since 2011. It’s so interesting to see how the text has evolved. I’d been thinking of putting something like this together myself, but wow! This is 1000x better than what I would have done. Working on Portuguese (Brazilian) and French versions now. Keep it up!

Thank you! 🙂

You’re working on Portuguese and French?? By which you mean cataloguing different editions and prints? I would definitely be interesting in seeing that!

Update: I’ve done some preliminary work on the Portuguese versions. My document is pretty sketchy looking compared to your great work and not doubt has a lot of holes. But so far I’ve found 17 editions between Portugal and Brazil. Anyway, I’m happy because I finally found the Brazilian kindle version to give to my wife so she can listen and read at the same time.

If you’re interested, here’s the Google doc with a table showing the different covers and years of publication, along with a comparison of the first two paragraphs of “The Boy Who Lived” and a few differences between them:

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1R3Q4z4h5NKbT7wnhOJ14YJUxPFTtwMPgYGblZ9PYP5s/edit?usp=sharing

Thank you! Thanks for sharing! I added a couple of comments.

Well, by “working on” I mean more currently reading. I was rather put off when I found out how different the audiobook in Brazilian Portuguese (2020) is compared to the e-book (2015). I got both so that my wife, who is interested in learning the language, could follow along reading while listening, but that’s impossible with how different the two are. I picked them both up using the links on Pottermore Publishing’s site under the Brazilian Portuguese filter, but apparently the link may have taken me to the Portugal Portuguese e-book and not the Brazilian Portuguese. I’m looking online, and there are numerous versions, many of them very expensive and hard to get in the US. Few are clearly labeled in which variety of the language they’re in.

Anyway, you’ve inspired me. Maybe I will create some sort of translation genealogy for the Portuguese versions. When it’s semi-presentable I’ll let you know. I’m a translator myself, and so different versions of things have always been very interesting to me.

That would be awesome! If you run across significant differences in different editions of the same translation, I’d definitely be interested in hearing about it!

Also if you have thoughts on the quality of the translations, I’d love to hear that too! Or even some specific examples that you thought were particularly well done or particularly poorly done. It’s all fascinating!